This month we spoke with composer Gareth Coker about his work on ARK: Survival Evolved. In 2016 Coker’s work for Ori and the Blind Forest was nominated for 6 G.A.N.G. Awards, winning 4 awards, including Rookie of the Year. He was also honored with the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences award for Outstanding Music Composition and SXSW Gaming Award for Excellence in Musical Score, and his success in the field led to him being recognized as an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music for his significant contribution to the music profession. We had a chance to talk about the process of composing for Steam Early Access titles, composing for large open world environments and working with orchestra.

What was it like working on a game in Steam Early Access? Did you find this had much of an impact on your composing process?

It was my first time working on an Early Access title, and it was the same for most members of Studio Wildcard, so there was an element of the unknown going in. Studio Wildcard always had a roadmap for the game, but no-one could have forseen the success of the game and that probably altered the roadmap a little. There are things I have learned from composing during this Early Access process that I would definitely apply into further titles. Most of all, I’d have tried to do a better job at anticipating the game’s musical needs from early access launch day. Mid-way through development we significantly altered how combat music played back in the game. Initially, there was just one combat track that occurred during day, and one combat during night. It was always planned that we would expand on this, as obviously, two combat tracks for an open world game is just not enough. We eventually had unique day/night combat music for each biome (ocean, cave, grassland, desert, mountain, snow, etc…). However, because gamers had been playing the game with just two combat tracks for well over a year, they had become used to the tracks and how they played back. Thus, when we changed things up, it wasn’t necessarily that the new music was ‘bad’, but it was affecting gamer’s experiences, expectations, and perhaps most importantly their memories. When one associates a positive experience with a piece of music (a raid, a tribe attack in-game, simply beating/fighting a dinosaur), you don’t want to do anything to potentially change or alter the memory of that positive experience. Changing the music does do this. So, in retrospect, I’d have tried to have super rough versions of all the biome combat music in the game. This isn’t always going to be possible as a game’s scope changes all the time, especially in early access, but it’s something I’ll definitely consider in the future.

The extension of this is that working on an early access title, can, (if you’re ‘lucky’!) result in something I’ve chosen to call ‘audience temp love’. Your earliest tracks for the game, what might be temp to you, the composer, ends up becoming a loved track by the audience. For example, we went through several iterations of the main theme for the game, and almost everyone preferred the very first ‘mocked up’ version. It wasn’t that the new versions were ‘worse’, it’s just that they were changed. There really has to be a significant and superior difference from your initial versions to your final versions. It’s a tricky balance because you’re wanting to keep your early access gamers title, but also remain true to your final vision, and also use the early access period to experiment.

Part of the process of working in Early Access is having gamers try out the game while its in development. What sort of feedback did you get from the gamers? How much of an input did they have?

Relentless feedback! On all aspects of the game! On the one hand this is great, but on the other hand, you’re dealing with a lot of noise, and you have to filter through to the issues that keep cropping up and try and solve them, similar to a triage system. However, as I implied above, you also have to take into account the original creative vision. For example, on release, ARK was probably perceived as ‘the dinosaur survival game’, even though there was a clear science fiction element in the game, which is very obvious through the game’s visuals and presentation, all that people would really see is “I can ride a dinosaur!”. About a year and a half through development the game took a major shift towards what they call the ‘TEK’ side, which adds a heavy layer of science-fiction elements and abilities. While this was always in the plan for the game, it altered the gameplay experience quite significantly for many. Inevitably, there was strong feedback on this development, but Studio Wildcard stuck to their vision.

This translates over to the music, though feedback can get confusing sometimes! On the one hand, gamers from the get-go were requesting more combat tracks, but then, when we put them in, people wanted the original combat tracks playing across the whole map (and many players had thought they’d been removed entirely, when they had just been assigned to the Grassland biome). One has to take the input, cross-check it with your own plans, and do one’s best to accommodate and integrate.

The final and perhaps most obvious benefit, is that ARK has been a huge success on Twitch. It’s such a huge game and almost impossible to test every scenario alone, so having Twitch streams and YouTube videos of people playing the game is a huge resource to have access to in terms of feedback. This is perhaps the biggest difference between early access development and traditional ‘closed’ development – there is a ton of ‘real’ information being generated every day by people playing your game.

Did you consider releasing the album before the full game came out? Was there any reason to release with game?

Did you consider releasing the album before the full game came out? Was there any reason to release with game?

While I didn’t have confirmation that the score would be recorded ‘live’, I made that assumption from the beginning due to the kind of game it was. I think we probably could have generated extra income by releasing the game’s ‘mockup’ music over the course of development, but ultimately, I don’t regard any of that work as the final product and thus I don’t want it to be endorsed by an official release, whereas the album of music (and in-game music that didn’t make it onto the official album) I do regard as a final product. I also am something of a traditionalist in that I don’t really like drip-feeding my work, and like to release things as a collection. The album – intense though it is – is meant to be listened to as a creative whole experience, and releasing music on a track by track basis would have mitigated that experience.

With such an extended score, and a huge game how did you make sure all the music linked together?

There are so many different scenarios in the game and so many different situations that there needed to be a few unifying elements in the score. First, and most obviously, the use of the main theme across several of the core combat tracks helps keeps things feeling consistent. It’s a consistent approach I’ve had across several soundtracks now to take one or two themes and develop them in as many ways as possible. There are so many ways to develop a theme and using various compositional techniques for this development can really help elongate a score and add coverage to the game. Second, was the use of the orchestra. It’s a unifying and familiar sound. Each biome has its own unique instruments and characteristics, for example, the swamp makes heavy use of the didgeridoo, the mountains make use of various ethnic wind instruments, but the orchestra can help unify things, and also give the ‘epic’ feel that the majority of players are expecting. Finally, and this is perhaps an overlooked element of the score – the music has a very strong tribal rhythmic element. Close examination of the rhythms used in the non-percussion and the rhythmic ‘stabs’ by the tonal instruments, are generally very close to tribal music from either the Pacific Islands, or Africa. It’s a more subtle, underlying thing, but given that ARK is largely a tribal game, it’s an element I wanted to add to the score.

What was the process like putting such a large collection of music together for an album?

It was a question of what to cut really. It actually wasn’t too hard. I knew I wanted to include the 3 core boss tracks – the Broodmother, the Megapithecus, the Dragon. The entire endgame experience needed to be included, especially as that is the only part of the game which is more linear and scripted. The Main Theme of course opens up the album. This left me about 50 minutes to fill and I was fortunate that the core battle music makes up almost all of this. The music that was cut was the seasonal music (Halloween, Christmas), and all of the ‘light mix’ combat music. All of the biome music had a full mix and a light mix which played during less intense combat (fighting a T-Rex is very different to … a dodo). At some point we’ll release all the remaining music, but probably not until the upcoming expansions DLC is finished.

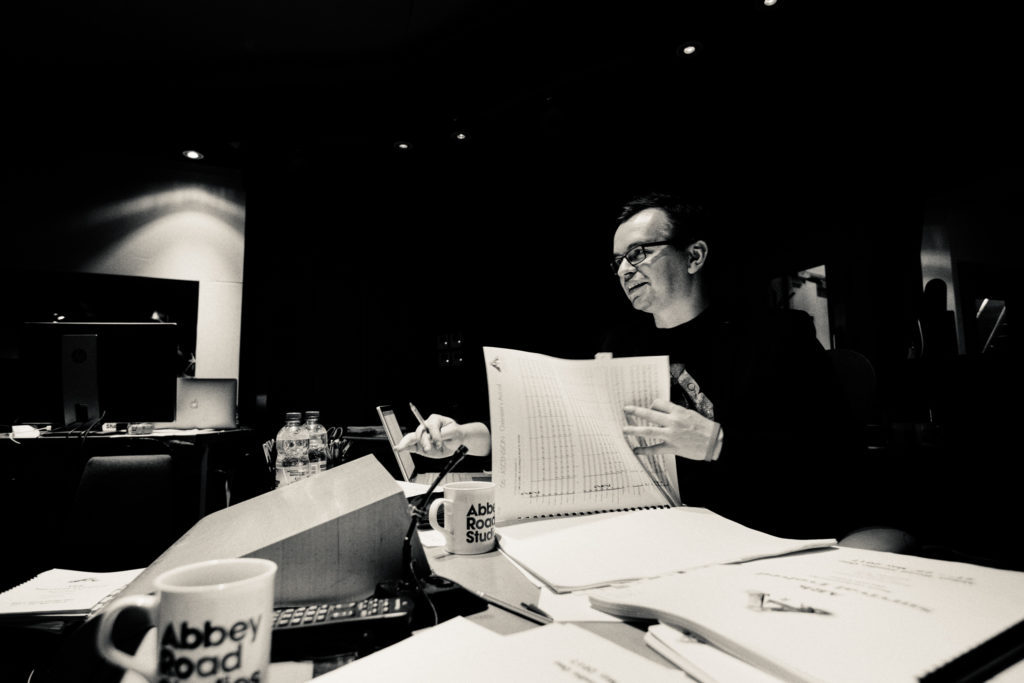

How did you handle spacing all the music of 3 days of recording? Any advice for people to work with a large orchestra in that setting?

While I have not recorded anything on this scale before, I do have enough experience recording to have a decent gauge for how much music we could get recorded in 3 days. We were also fortunate to have the Philharmonia Orchestra, who are a world-class group with unbelievable sightreading abilities. Additionally, we were able to save significant time by not recording sections separately for the majority of cues. About 80% of the music is everyone in the room together at the same time, which definitely cuts down on recording time needs.

If you’re working with a large orchestra, ideally whoever is conducting needs to have a fantastic understanding of session etiquette, which is very different to working in a traditional concert setting. The players will usually be able to help with this, but you also need a conductor who can read the room, and pick up the pace when necessary, but also zero in on things and slow the pace down, or just choose when to take a break if and when it’s needed. It’s not an exact science, and for me, the role of conductor is incredibly important, especially as a communicator but also in terms of keeping the orchestra interested and motivated. I think chemistry is a very important ingredient for creating and recording music, and it’s something that can be subconsciously felt by the musicians when they are playing. If the atmosphere between the core team is strong, it’ll carry over to the musicians. This obviously has a huge effect when the orchestra is as big as the one we used for ARK – 93 musicians!

My other main advice would be to hire help. It gets to a point where it is physically impossible to do everything yourself. You absolutely need to make sure you have a group of people around you who you know and trust and also can understand your creative vision. I’m very fortunate that I’ve known two of my core team, Alexander Rudd, my conductor and Zach Lemmon, my additional eyes and ears, since 2010, and they’ve been with me at some point on all of my previous work. It gets to the point where they can see fires before they happen which allows you to focus on your job, which is getting the music and the recording right. You also need to have your logisitics completely solidified, there’s a lot of data flying around, Pro Tools files, Sibelius files, stems, file versions, and then the printing, binding, taping. There’s no way a composer should be organizing that, and fortunately, we have a massive community – especially here within GANG – of people that can help in just about every facet of recording, so don’t be afraid to ask and reach out!

The ARK: Survival Evolved soundtrack is now available on all digital and streaming outlets through Sumthing Else Music Works.