RARELY IN THE WORLD OF GAME SCORING do pieces of music appear as they were originally written. Whether edited to loop, or for interactivity or content, a big part of preparing music for implementation is the process of additive or subtractive music editing. There isn’t much middle ground with music editing. Bad edits are glaringly obvious and unmusical while good edits are completely undetectable.

RARELY IN THE WORLD OF GAME SCORING do pieces of music appear as they were originally written. Whether edited to loop, or for interactivity or content, a big part of preparing music for implementation is the process of additive or subtractive music editing. There isn’t much middle ground with music editing. Bad edits are glaringly obvious and unmusical while good edits are completely undetectable.

THE BASICS OF BLENDING

The simplest way to edit two pieces of music together is by using a basic crossfade at the join. Music which uses the same time signature and at the same tempo (which is the case for most pop/rock music as well as most game scores) is the easiest to tackle with basic crossfades. Simple crossfades have a number of benefits. All digital audio workstations (DAWs) such as Pro Tools or Logic make authoring crossfades easy with click-and-drag crossfade tools. These tools offer a limited ability to edit the shape of the fades, though editing one part of the fade will affect the entire crossfade curve. Additionally, simple crossfades lack the dangers of radical changes in amplitude that come from more advanced edits such as layering multiple tracks together and summing their outputs.

The size of a crossfade depends on what’s going on musically at the join. If you’re simply editing out a verse from a pop tune, the crossfade will most likely be fairly short and centered on a moment of identical orchestration, such as a repeated guitar riff, or you may splice together a syncopated drum accent. Crossfading between arrhythmic pads or long decay tails will most likely benefit from longer crossfades that approximate the dovetailing of one completed musical thought and the beginning of a second thought.

Simple crossfades can have their problems, as melodies that don’t begin on barlines or long cymbal swells are more difficult to tackle with a simplified crossfade tool. In these cases, the join of your edit will probably not be the center point of the crossfade. Rather, you may find the fade beginning a few beats before or ending a few beats after the join in order to ease into or out of sections with troublesome instrumentation or lingering high frequency noise.

THE SCIENCE OF SHAPING

A simple crossfade can only do so much, though. More advanced music editing necessitates a complex understanding of orchestration, acoustics, and studio mixing techniques. Though more involved, these methods can turn an impossible crossfade into a successfully indistinguishable edit.

You can move beyond basic crossfades by layering multiple tracks. Layering tracks allows for the combination of multiple source sounds, each of which can have its own fade properties. This kind of editing is extremely helpful when working with orchestral material that changes its tempo or time signature repeatedly. Editing in layers allows the music editor to introduce new material without fading out the original. This can be done to add musical elements that weren’t present in the original piece such as dissonant brass clusters, rhythmic ostinatos, or simply percussion sweeteners like timpani rolls or cymbal swells that can smooth over edit joins.

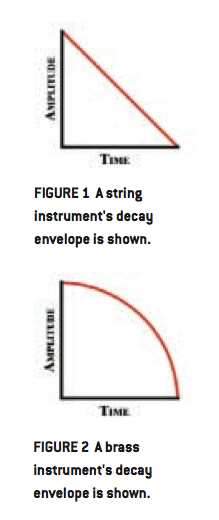

Editing on separate layers also allows for the creation of individual fade curves. A brass line may be made to taper out musically or a string glissando can crescendo independent of the rest of the musical material. Doing so necessitates an understanding of natural acoustic amplitude envelopes. Strings, for instance, fade in and fade out very naturally through the use of a basic linear fade (see Figure 1). Woodwinds and brass, however, sound extremely unnatural with a linear decay. Breath- based instruments are much better served with logarithmic amplitude decay envelopes (see Figure 2).

Another thing to keep in mind when layering multiple tracks is the relative volume of your layers. Sometimes simply raising or lowering the volume of the target piece of music so that it better matches what came before can fix an awkward edit. Likewise, individual volume curves can be edited to create melodic crescendos or decrescendos that feel as if they are a natural part of the original composition. However, overall volume levels can become an issue when layering tracks together. Unlike crossfading on a single track, layering means that the amplitudes of multiple source files are being summed together out of the main output. The result is often a spike in volume that can clip and send your meters into the red. To combat this, the music editor can either lower all of the individual volume levels for the separate layers or rely on the addition of a limiter into the signal chain to help keep the track from peaking.

THE LOGIC OF LOOPING

One last point about music editing for games: always keep in mind that the beginning of a piece of music becomes arbitrary when it becomes an in-game loop. Once a track is edited and stitched together from end to end, reverb tails, cymbal swells, or nuances in production work might mean that what once was the beginning of the track now isn’t actually the best place to edit the loop’s start point. Don’t discount starting loops with a melodic pickup or a glissando. Frequently, these starting points go unnoticed as loop points once the end of the file has been reached.